Waterberg - A UNESCO Biosphere

Waterberg Biosphere Reserve is situated within the Bushveld district in the Limpopo Province of South Africa. The Waterberg, as the name implies, serves as a water reservoir for this arid region. It is an area consisting of low mountain ranges and escarpments with poor soils and a relatively low level of economic activity. The vegetation is dominated by different veld types, which are characteristic in mountainous savanna areas. You will find that the Waterberg Mountain Range is the ideal getaway where the weary traveller can relax and revel in the great natural beauty of the bushveld savannah and its rich wildlife heritage.

The Waterberg Mountains stretch along more than 5 000 km² of spectacular vistas and scenic valleys - the ideal destination off the beaten tourism track.

Interested in exploring the Warterberg Region?

About the Waterberg

The Waterberg Biosphere is a massif of approximately 15,000 square kilometers in north Limpopo Province, South Africa. Waterberg is the first region in the northern part of South Africa to be named as a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO. The extensive rock formation was shaped by hundreds of millions of years of riverine erosion to yield diverse bluff and butte landform. The ecosystem can be characterized as a dry deciduous forest or Bushveld. Within the Waterberg there are archaeological finds dating to the Stone Age, and nearby are early evolutionary finds related to the origin of humans.

The underlying rock formation derives from the Kaapvaal craton, formed as a precursor island roughly 2.7 billion years ago. This crustal formation became the base of the Waterberg, which was further transformed by upward extrusion of igneous rock. These extruded rocks, containing minerals such as vanadium and platinum, are called the Bushveld igneous complex. The original extent of this rock up thrust involved about 250,000 square kilometers and is sometimes called the Waterberg Supergroup.

Sedimentary deposition from rivers cutting through Waterberg endured until roughly 1.5 billion years ago. In more recent time (around 250 million years ago) the Kaapvaal craton collided with the supercontinent Gondwana, and split Gondwana into its modern-day continents. Waterberg today contains mesas, buttes and some kopje outcrops. Some cliffs stand up to 550 meters above the plains, with exposed multi-colored sandstone.

The sandstone formations could retain groundwater enough to make a suitable environment for primitive man. The cliff overhangs offered natural shelters for these early humans. The first human ancestors may have been at Waterberg as early as three million years ago, since Makapansgat, 40 kilometers distant, has yielded skeletons of Australopithecus africanus[1]. Hogan suggests that Homo erectus, whose evidence remains were also discovered in Makapansgat, “may have purposefully moved into the higher areas of the Waterberg for summer (December to March) game”.

Bushmen entered Waterberg around two thousand years ago. They produced rock paintings at Lapalala within the Waterberg, including depictions of rhinoceros and antelope. Early Iron Age settlers in Waterberg were Bantu, who had brought cattle to the region. The Bantu created a problem in Waterberg, since cattle reduced grassland caused invasion of brush species leading to an outbreak of the tsetse fly. The ensuing epidemic of sleeping sickness depopulated the plains, but at higher elevations man survived, because the fly cannot survive above 600 meters.

Later people left the first Stone Age artifacts recovered in northern South Africa. Starting about the year 1300 AD, Nguni settlers arrived with new technologies, including the ability to build dry-stone walls, which techniques were then used to add defensive works to their Iron Age forts, some of which walls survive to today. Archaeologists continue to excavate Waterberg to shed light on the Nguni culture and the associated dry-stone architecture.

The first white settlers arrived in Waterberg in 1808 and the first naturalist a Swede appeared just before mid-19th century. Around the mid-19th century, a group of Dutch travelers set out from Cape Town in search of Jerusalem. Arriving in Waterberg, they mis-estimated their distance and thought they had reached Egypt.

After battles between Dutch settlers and tribesmen, the races co-existed until around 1900. The Dutch brought further cattle grazing, multiplying the impacts of indigenous tribes. By the beginning of the 20th century there were an estimated 200 western inhabitants of the Waterberg, and grassland loss began to have a severe impact upon native wildlife populations.

Other indigenous mammals include giraffe, white rhinoceros and warthog. Snakes include the black mamba and spitting cobra. In 1905 Eugene Marais studied these snakes of the Waterberg. Some birds seen are the Black-headed oriole and the White-backed vulture. Predators include the Leopard, Hyena, and Lion.

Vegetative cliff habitats are abundant in the Waterberg due to the extensive historic riverine erosion. The African Porcupine uses the protection of these cliffside caves. Some trees cling to the cliff areas, including the Paper tree, whose flaking bark hangs from their thick trunks. of specimens clinging to cliffsides above winding streams below. Another tree in this habitat is the fever tree, thought by Bushmen to have special power to allow communication with the dead. It is found on cliffs above the Palala River including one site used for prehistoric ceremonies, which is also a location of some intact rock paintings.

Riparian zones are associated with various rivers that cut through Waterberg. These surface waters all drain to the Limpopo River which flows easterly to discharge into the Indian Ocean. Red bush willow is a riparian tree in this habitat. These riparian zones offer habitat for birds, reptiles and mammals that require more water than plateau species. The riverine areas house the apex predator Nile crocodile and the hippopotamus. These wet habitats are almost absent of water-related insects, and the Waterberg is thus considered an almost Malaria-free region.

As of 2006 about 80,000 people live in the Waterberg, which is considered part of the Bushveld district of the Limpopo Province of South Africa. After cattle grazing wrought ecological havoc in the mid-1900s, the land owners of the region became aware of the benefits of restoring habitat to attract and protect the original species of antelope, white rhino, giraffe, hippopotami, and other species whose numbers dropped in the era of intense cattle grazing.

The rise in eco-tourism has stimulated interest in soil conservation practices to restore original grass species to the Waterberg. Land management practices required are expensive but repay the landowner with added value of wildlife habitat. There is also a trend of larger farms and open space areas with the resultant advantage of fence removal. This outcome not only benefits large mammal migration but yields an improved gene pool.

The Waterberg Biosphere is steeped in a history and some artefacts found here date back to Stone Age times. The area is a mosaic of culture and tradition as is reflected by the different rural tribes such as the Bapedi, Tswana and Basotho, while the Voortrekkers also left their distinctive mark on the area.

Commercial agriculture is an integral part of Limpopo, and cattle ranching and maize farming are regional institutions - the water-rich valleys of the Limpopo River on the Botswana border provide sweet bushveld grazing.

Otherwise, the bushveld landscape, interspersed with sandstone buttresses and baobab, Marula and fever trees, supports a few towns that make up one of the country's fastest-growing industrial and agricultural districts. The Waterberg is one of the most mineralised regions in the world and numerous towns form part of the Bushveld Igneous Complex - 50,000km² treasure trove yielding massive amounts of minerals such as vanadium, platinum, nickel and chromium.

The Waterberg Biosphere and District offers the tourist a bit of both worlds - an infrastructure of excellent facilities and modern conveniences found in the many game reserves and conservation areas, coupled with the opportunity to experience the African wilderness in its pristine state.

In 2001 a third of the plateau (6 524 km²) was designated by UNESCO as the Waterberg Biosphere Reserve and more recently Birdlife South Africa has recognized the entire Waterberg as a globally recognized Important Bird & Biodiversity Area (IBA). As examples of the value of the Waterberg for biodiversity, populations of about 2000 plant species occur here, of which about 30 are range-restricted, rare or endangered; mammal species recorded number 119, reptile species 98, bird species 447, butterfly species 242, dragonflies and damselflies 91, and so on.

One of Birdlife South Africa's goals is to enhance and promote the conservation status of the Important Bird & Biodiversity Areas in South Africa and the purpose of this website is to assist in this endeavor for the Waterberg. We aim to provide a resource that documents and illustrates the fauna and flora of the region, helps pinpoint critical biodiversity areas and, for added interest, provides visual, descriptive and reference information on the Waterberg's geology, geomorphology, landscapes and history. The website is very much a work-in-progress and any participation, information or other contributions to the project are welcomed - if you have photos of any interesting aspect of the Waterberg and are prepared to have them included in this site, please let us know.

Some 77,000 people live in the biosphere reserve (1999), which covers an area of about 400,000 hectares. The area has been inhabited over hundreds of thousand years and is one of the most important San Rock Art areas in South Africa. Tourism is the major source of income. However, people also practice cattle rising, crop production and are increasingly switching over to game farming for eco-tourism.

The biosphere reserve concept will help a balance to be struck between the pressures of the tourist industry, the need to generate direct benefits to the local communities and the conservation of the natural assets. Attaining this balance is the goal of the Waterberg Biosphere Reserve Committee which was set up after a five-year consultation process with all stakeholders concerned. A series of technical action plans have been elaborated among which also environmental education programmes play an important role, led by the Lapalala Wilderness School.

Major Habitats & Land Cover Types

Sour Bushveld characterized by African Beechwood (Faurea saligna), Common Hookthorn (Acacia caffra), Red Seringa (Burkea africana, Terminalia sericea and Peltophorum africanum) etc.; steep slopes and cliffs, bare rock including the same tree species as mentioned above and with Albizia tanganyicensis and Combretum molle characteristic of the rocks; river-bank and freshwater habitats including wetlands, characterized by Mimusops zeyheri, Clerodendrum glabrum, Ficus thonningii etc.; cattle raising and game farming; irrigated tobacco cultivation; human settlements.

There are several sub-habitats within the Waterberg Biosphere, which is fundamentally a dry deciduous forest; These sub-habitats include high plateau savanna, specialized shaded cliff vegetation system and riparian zone habitat with associated marshes.

The savanna consists of rolling grasslands and a semi-deciduous forest, with trees such as Mountain seringa, Silver-leaf terminalia and Lavender tree. The canopy is mostly leafless during the dry winter. Native grasses include Signal grass, Goose grass and Heather-topped grass. Indigenous grasses provide graze to support native species including impala, kudu, klipspringer and Blue wildebeest. Some Pachypodium habitats are found especially in isolated kopje formations

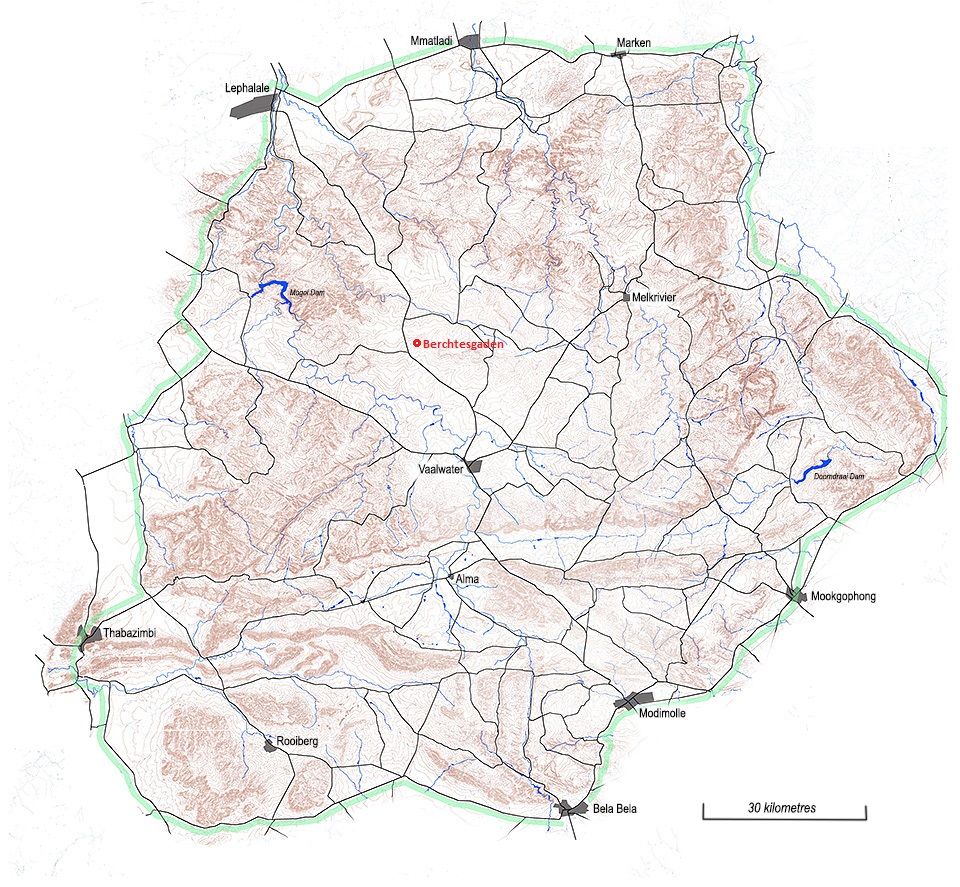

The map below outlines the area of interest, the outer perimeter demarcated in green. This map shows, too, the parts that are hilly or mountainous (brown), the towns and villages in the area (dark grey), the network of tarred and gravel roads (black lines) and the main rivers (blue lines).